The Inevitability of RPA in Finance and Accounting – Changing Labor Force

Blog post

Share

Over the next five years a sea-change will be taking place across multiple industries which will impact hundreds of thousands of finance and accounting professionals. The very nature of our business and day to day activities will change as manual “human in the middle” processes give way to rules-based automation, then to machine learning and ultimately to neural cognitive automation. The objective of this 3-part blog series is to frame the three undercurrents of this transformation and to align forward looking finance and accounting professionals around the new reality. We begin this analysis with a consideration of the unassailable changes to our demography and the challenge to institutional knowledge.

There are three fundamental “meta-trends” which are at play when we with think of the shifting demography in the global workforce and it’s impact on the business of Finance and Accounting.

I. The Aging Labor Pool

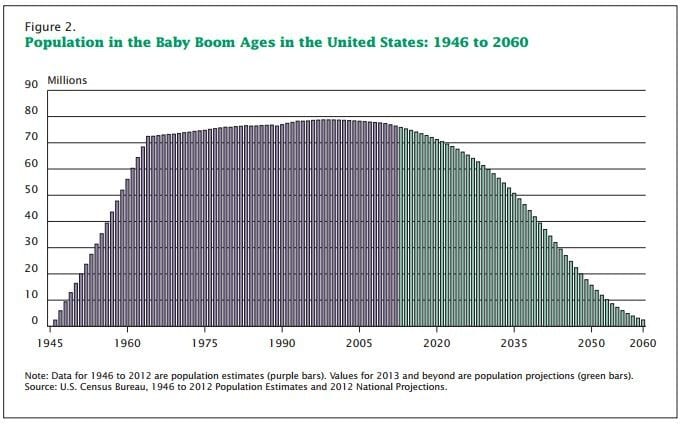

According to the 2015 US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the labor force in the United States continues to age, with the median age now 41.9 years and a projected age 42.5 years by 2024. At the same time the labor force participation rate is expected to decrease from the present 62.9% to 60.9%. The underlying cause for this change may be largely attributed to the aging and eventual exit of the “Baby Boomer” generation from the labor pool. “Baby Boomers, as they are known, are notionally the population cohort born from 1947 to 1964. At its peak in the mid-1990’s the US Census Bureau estimated that nearly 80 Million “Baby Boomers were in the labor force. In 2016 the average “Baby Boomer” turned 60 years old, as such the departure of this massive labor cohort is now accelerating at a rate which will place tremendous strain on business. In fact, commonly accepted statistics cited by the US Social Security Administration and Pew Research indicate that a stunning 10,000 Baby Boomers retire every day here in the United States!

According to the 2015 US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the labor force in the United States continues to age, with the median age now 41.9 years and a projected age 42.5 years by 2024. At the same time the labor force participation rate is expected to decrease from the present 62.9% to 60.9%. The underlying cause for this change may be largely attributed to the aging and eventual exit of the “Baby Boomer” generation from the labor pool. “Baby Boomers, as they are known, are notionally the population cohort born from 1947 to 1964. At its peak in the mid-1990’s the US Census Bureau estimated that nearly 80 Million “Baby Boomers were in the labor force. In 2016 the average “Baby Boomer” turned 60 years old, as such the departure of this massive labor cohort is now accelerating at a rate which will place tremendous strain on business. In fact, commonly accepted statistics cited by the US Social Security Administration and Pew Research indicate that a stunning 10,000 Baby Boomers retire every day here in the United States!

II. The Emergence of the Millennial Generation

“Millennials”, as they are referred to, constitute the population cohort born from 1981 to 1997 and whose early life experiences were influenced by events in the late 1990’s through the mid 2000’s. It is this population cohort which is now entering the labor market at an accelerating rate. In fact, according to Pew Research the Millennial generation surpassed the Baby Boomers and Gen-X (those born between 1965 and 1981), as the largest cohort within the US Labor Force. In a general sense, this is encouraging – the notion of one generation retiring while another steps in to pick up the baton. However, the Millennial generation is unlike any of its predecessors. Raised on technology and with a transactional view of the work-life relationship, there are some very interesting dynamics here. Consider the following:

- A May 2016 Gallup Poll survey indicated that 60% of all millennials are open to a new job.

- This same poll indicated that almost 25% of millennials had changed jobs within the prior year, a rate that is three times higher than the number of non-millennials reporting the same.

- Gallup also found that about 3 in 10 millennials would consider themselves “engaged in their work”, a number far lower than the traditional number

It is no wonder why the millennial generation can be seen as “consumers of the workplace”. What can be drawn from this data? It is evident that business’ can expect and should prepare for a more fluid labor pool going forward as millennials view the relationship with their employer to be more transactional in nature. It is here that the complex nature of Finance and Accounting, labor, and the necessity for automation intersect and our third meta-trend around demography.

III. The Erosion of Institutional Knowledge

Acknowledging the aforementioned “changing winds” in the labor pool and the very different way that the emerging working-age employees tend to view their participation in their careers, business’ in general are hugely exposed to degradation of their institutional knowledge (IP). It’s no secret that Finance and Accounting (F&A) professionals relied heavily on manual processes and office automation tools, including the ubiquitous Microsoft Excel, to perform their critical period-end activities. In fact, a survey by Financial Executives Research Foundation and Robert Half, indicated that 66% of all companies still manually reconcile their general ledger accounts. Logic dictates that such a process relies heavily upon the experience and institutional knowledge of accountants, but how can an enterprise be expected to ensure that this process works smoothly and without error when the wizened “elder-statesman” just retired and the new, energetic go-getter does not seem compelled to fully engage? In general, the capture and retention of Institutional Knowledge is now a consuming passion for forward-thinking leaders. In fact, Harvard Business Review identified some best practices for consideration. However, I would argue that we must look beyond simply recording the past and we must consider how we might capture this knowledge in a framework which would allow us to encode the very best of our core F&A knowledge and carry it forward.

In our next blog, we will review why the business cycle, macro-economic and even regulatory environment is now ripe for Finance and Accounting to fully embrace the emerging Robotic Process Automation trends.

Written by: Ben Cornforth